Start, Stabilise, Scale: A basic guide to modular kitchen manufacturing

Kitchen and wardrobe work in many towns and cities across India is changing fast. Not long ago, most of it was done by carpenters on site with simple tools and a lot of manual skills. Today, more of that work is shifting into factory-style units with machines, software and organised teams. Customers expect a cleaner finish, better use of space and shorter waiting times.

For manufacturers, this change brings both opportunity and pressure. There is clear demand for good factory-made cabinets, but a wrong decision about machines or layout can lock up money and slow down growth for years. The question is no longer, ‘What machine should I buy?’ It is also, ‘When should I buy it, for which market, and with what process behind it?’

Across different scales of business, a few themes keep coming back: clear written processes instead of only verbal instructions, a stronger after-sales mindset, and smarter use of material and energy.

Mapping location

Before thinking about new equipment or a new factory, it helps to read the market in a simple but honest way. For cabinet work, distance on a map matters less than the time it takes to reach a site and come back. A factory inside a crowded zone, or in an area with strict rules for truck movement, can be hard to service even if it is close by.

Another location slightly farther away, but on a clear route, may work better. Thinking in terms of minutes, not km, gives a more realistic picture of how installation and delivery will work in daily life.

The buildings around you tell another part of the story. New housing projects with bare or semi-bare kitchens and wardrobes create one type of demand. Older neighbourhoods, where people remove old carpentry and shift to modular work, create another.

New projects often bring more standard and repeat modules, while renovation areas bring odd sizes and tricky walls that need more checking and more care.

It also matters who is serving these customers today. In many markets, independent carpenters still do most of the work, and a factory can become their back end for ready-to-fit parts. In other areas, large showroom-based players are active, and a local manufacturer may be better off standing out with flexibility, custom sizing and faster, more personal service rather than trying to look like a national brand.

Investment dilemma

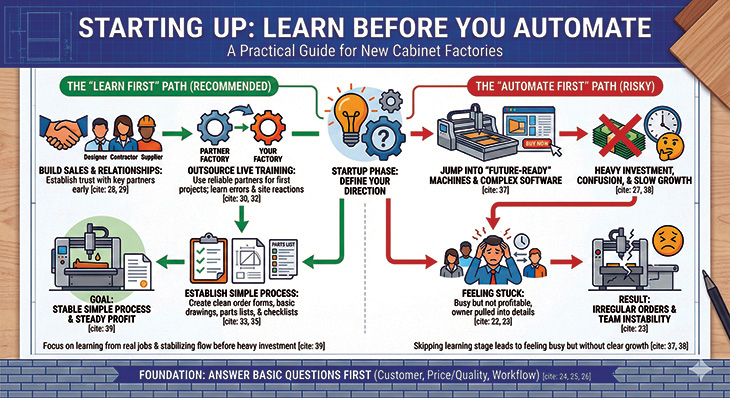

When a new factory-size manufacturing unit is being planned, the first attraction is usually the machine brochure! It is easy to believe that once a nesting machine or an automatic edge bander is installed, everything will fall into place.

Many new factories feel stuck after a big purchase. The monthly payments run on time, but orders remain irregular, the owner is pulled into every small detail, and the team keeps changing.

A startup needs to answer some basic questions clearly. Who is the main customer: end users, interior designers, small builders, or a mix of all three? What price and quality level will the factory play in? How will work move from enquiry to drawing, then to cutting, then to installation?

Until this picture is clear, heavy investment can create more confusion than growth. That is why early effort is better spent on sales and relationships than on metal. The aim in the first phase is to build trust with designers, contractors and suppliers who are likely to stay with the factory for a long time.

One practical way to do this is to outsource the first few projects to a reliable partner. On paper, this looks like a loss because some margin goes to another factory. In practice, these jobs act as live training.

They show how drawings are read, how errors really happen, which steps create most rework and how sites react when things do not fit the first time. After a few real projects have been seen from start to finish, the goal is not to copy the outsource partner, but to design a simple process that suits the new business.

At the beginning, this process does not need a thick manual. It needs a clean order form, a basic drawing format that customers sign before work starts, a simple list of parts and materials for each job and a short checklist before despatch and installation.

These small documents prevent a lot of confusion and arguments later. Many new factories skip this stage and jump straight into “future-ready” machines and complex software without firm answers to basic questions.

They feel busy, but do not see steady profit or clear growth. A safer path is to learn through real jobs, stabilise a simple process, and then invest in machines that support that process instead of trying to replace it.

Fix the flow

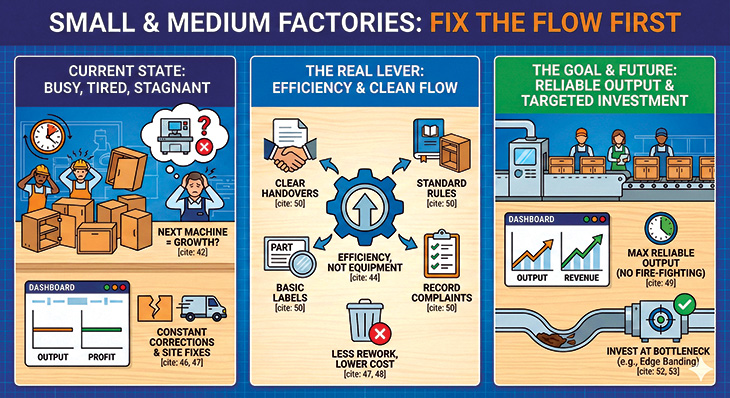

Small and medium factories face a different kind of challenge. Many of them already own more than one major machine. The owner often thinks about the next machine as the key to growth but feels that the business is stuck at roughly the same level as before. The shop is busy, people are tired, but the numbers do not move in the way everyone hoped.

In many such units, the real lever is efficiency, not more equipment. A quick health check of the current process can be very revealing.

If production teams are constantly doing corrections and revisions, if half-done jobs are lying on the floor, if design issues are being discovered during cutting or assembly, and if fitting teams keep going back to site to fix small but painful mistakes, then the factory does not need more machines; it needs fewer errors and cleaner flow.

Each remake and each extra visit is not just a quality issue – it is also extra cost, slower turnaround and more pressure on after-sales.

For a small or medium-sized factory, a good goal is to get the maximum reliable output from one normal shift with the machines that already exist, and to do this without daily firefighting.

Simple moves such as clearer hand-over from sales or design to production, standard rules for common cabinet sizes, basic labels on parts so they do not get mixed up, and a short record of site complaints reviewed regularly can together make a big difference.

Once these basics are in place, real bottlenecks become easier to see. It may become clear that cutting is always behind, or that drilling is slowing things down, or that edge banding is the true choke point. At that moment, investing in one more machine at the right step can genuinely increase capacity and revenue, instead of just adding noise.

Adopting systems

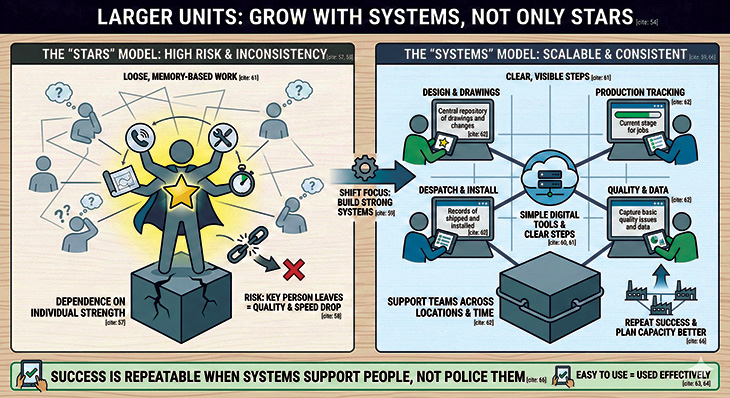

Larger units, including bigger MSME and enterprise-style manufacturers, usually have another kind of problem. Most of them already have good machines and defined steps on paper. Their struggle is to get the same way of working every day, across different teams, shifts or locations.

When a business depends heavily on a few star people, the risk is high. If one key person leaves or moves, quality and speed can drop sharply.

At this level, the focus must move from individual strength to strong systems. Simple digital tools can help, but only if they are used in a practical way. Going digital does not mean replacing people with software. It means moving from loose, memory-based work to clear steps that everyone can see.

Systems that store final drawings and changes in one place show where each job has reached in production, record what has been despatched and installed, and capture basic data on quality issues can support teams across locations and over time.

The most important point is that such systems must be easy to use. A tool that looks impressive but feels confusing must be avoided or updated late.

A simple screen that matches the real day-to-day flow is far more powerful than a complex one that nobody trusts.

Larger units that treat digital tools to support people – not to police them – can repeat their success more easily in new teams or new cities and can use data from all locations to improve products and plan capacity better.

Building sustainability

Alongside process and after-sales, sustainability can also be built into daily work in a practical way.

In cabinet manufacturing, three areas matter a lot: material waste, energy and dust, and the way materials are chosen for each job.

Panel waste is often one of the largest hidden costs in a factory. Every offcut is money lying on the floor. With a little planning, many factories can cut this waste and save cost at the same time.

Planning jobs so that boards of the same colour and thickness are cut together and having a clear way to store and label offcuts that are big enough to reuse, can help. These pieces can then be used for smaller parts, internal shelves, packing or sample units, instead of going straight to scrap. Reducing rework also helps here, because every remake doubles the material used for the same job.

Clean air in the workshop is good for people and machines. Dust that floats in the air or settles everywhere affects lungs, bearings and final finish. A simple, well-maintained dust extraction line and regular cleaning routine make a real difference. Energy can also be managed with basic habits like switching off idle machines and lights.

Material choice is another quiet but powerful lever. There is no single “best” board or hardware for all jobs. What matters is matching the material to the use. Cabinets near sinks or cooking areas have different needs from wardrobe interiors. Heavily used drawers need stronger hardware than a rarely used loft. A job that fails early because of poor material choice, weak hardware or wrong detailing creates extra waste, extra work and unhappy customers. A slightly better specification, used wisely, can keep the product working well for many years.

Simplify processes

Factory-based cabinet manufacturing is likely to keep growing as more customers ask for better finish and faster work. But good machines alone do not build a strong business. At the startup stage, the most powerful step is to learn from real jobs and build a simple, stable process before making heavy investments. For small and medium factories, the main lever is to improve efficiency and reduce rework, instead of running behind the next machine. For larger units, the focus shifts to systems and simple digital tools that keep work consistent across teams and locations.

Across all scales, clear written processes, a serious approach to after-sales and everyday decisions that reduce waste and support sustainability form the base. Manufacturers who work on these foundations are more likely to stay strong as the market continues to grow and change.

– The writer is a woodworking industry veteran, with more than 10 years in consulting (Schuler), software development (Homag), data analytics and sales. He helps furniture manufacturers plan factories, introduce digital tools, scale up production and enable sustainable growth. For more information, write to contact@vikash-sharma.com.

- European symposium highlights formaldehyde emission limits

- Egger adopts holistic approach to waste management

- Taiwan’s Woodworking Machinery Industry Captivates Global Media on Opening Day of LIGNA 2025

- Coming of age of sustainability

- Intelligent packing line, sander from Woodtech

- Ornare introduces 5 new leather decors

- Richfill Edge Coat offers safer plywood finishing

- Jai’s Optimus range stays ahead of the curve

- Merino’s Acrolam sets new benchmarks in elegance

- Pytha 3D-CAD: where precision meets production

- Raucarp edge bands: simple, affordable

- Greenlam scores a 1st: High Quality Product Award

- Häfele turns space solutions provider

- Hettich bets on intelligent motion for evolving interiors

- Praveedh taking desi innovation to the global stage

- Turakhia shows off its Natural Veneers range

- Egger continues to ‘inspire, create, grow’

- Blum turns heads with new drawer, hinge systems

- Vecoplan tailors waste wood processing at Schaffer Holz

- Biesse starts training at HPWWI Mumbai

- HIFF 2025 underscores growing furniture capabilities

- Osaka Expo celebrates forests for humans

- CIFF Guangzhou 2026: connecting to create

- Feria Hábitat announces dates for 2026 show

- ‘Digital twins’ streamline factory planning, commissioning

- Smart illumination weds wood veneer

- Vecoplan ushers intelligent vibes

- New bio-based adhesives for particleboard

- Digital timber-tracking rolls across Poland

- Chitosan-rosin combo: flame-retardant adhesive

- Chicken coup: turning feathers into wood glue

- Start, Stabilise, Scale: A basic guide to modular kitchen manufacturing

- Fast Forward: surface tech attains maturity

- ‘Smart’ experiment unravels cooking behaviour

- Blum cabinet hinges earn BIS approval

- Ebco has smart storage solutions

- Hettich has holistic kitchen solutions

- Hexagon brings digital precision to manufacturing

- Leitz takes on modern materials, finishes

- Mirka’s smart tools for superior finishes

- Protego tabletop oils protect surfaces

- Top-class finishing: Woodmaster tells you how

- Keen to cut it right for India: Freud’s Andrea Komadina

- ‘Rainbow tools’: functionality or hype?

- Pidilite’s practical skilling initiative for modern joinery

- PVA adhesives: weather-ing challenges in India

- How loyalty plays in Tier-2/3 ply, laminate markets

- AHEC’s ‘Days of Design’

- IndiaWood 2026 to showcase Indian capabilities